Corentin Derbré

Books:

An Architectural Approach to Level Design – Christopher W. Totten

ISBN: 1466585412

Date read: 2016-04-10

How strongly I recommend it: 5/10

(See my list of books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Good overview on the topic, but not going in depth, no advanced descriptions, and no conclusion.

my notes

An Architectural Approach to Level Design – Christopher W. Totten

ISBN: 1466585412

Date read: 2016-04-10

How strongly I recommend it: 5/10

(See my list of books, for more.)

Go to the Amazon page for details and reviews.

Good overview on the topic, but not going in depth, no advanced descriptions, and no conclusion.

my notes

Chapter 1: A Brief History of Architecture and Level Design

Vitruvius considered firmitas (firmness), utilitias (utility), and venustas (delight) to be the vital elements of architecture.

Gamespaces must be usable. In this way, we should concentrate on how players see gamespace through points of view and game cameras and how one navigates levels. This element of level design concentrates on navigation and teaching. As we will see, levels are an opportunity for game designers to have an indirect conversation with players. As such, our game levels should teach players how to use themselves and speak in easily understood language.

Gamespaces should be rewarding to go through. Levels guide players through emotional experiences. Players have control over climactic events of the game.

Also look down—is the space’s verticality used in reverse to make you feel in danger?

Chapter 2: Tools and Techniques for Level Design

Skill gates are required challenges that block a player’s progress unless he or she performs a specific action to pass.

Persuasive games. These games communicate a message or teach players something through gameplay.

This turns game levels into systems of rhetoric, the art of communicating ideas through discourse. Games make their arguments through the cause-and- effect relationships between player actions and game rules.

Levels can give informa- tion to players in ways that allow them to make informed decisions about what is coming next. Lighted signs in Valve Corporation’s Portal tell play- ers what mechanics a given puzzle will involve at the entrance to every chamber. Patterns in level design can inform players when bosses or other significant enemies are coming.

Chapter 3: Basic Gamespaces

Considerations of camera.

Suspens. A favorite example of Hitchcock’s was to propose a scene where two people were sitting at a table, but the camera pans down to show that a bomb is underneath. That the diners do not know of the impending doom instills the scene with suspense for the audience that does get to see the bomb.

Chapter 4: Teaching in Levels trough Visual Communication

Players should be only set back to a point where they can comfortably retry a challenge.

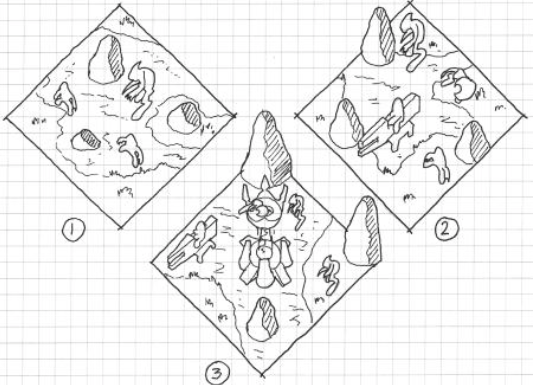

This diagram illustrates several different enemy strongholds created with a modular set of assets. Recognizable assets allow players to use Montessori- style understanding of the level to form strategies. The checkpoints at the beginning of each challenge help create an iterative problem-solving play style.

Objects in video games: they are not actual objects but are visual representations of objects.

Architect Adolf Loos, in a 1910 lecture, famously argued, “Ornament is a crime.”26 The rationale for this, argued in rebuttal to the ornate art nouveau movement, was a belief that ornament could limit an object’s stylistic longevity, and that the use of ornament was therefore unethical.

Framing describes the use of foreground elements to surround the view of something important in an environment as though it were in a frame.

Building types as modular assets: the buildings communicate through their building type and are reusable from town to town. While Skyrim’s wealth of detail allows many buildings to be unique, consistent elements like those mentioned above still allow these buildings to communicate their function to players.

Demonstrative Advertising with Scripted Events and Triggers. In-game demonstrative scenarios show players how hazardous gameplay elements work in a safe way so that players can build associations.

Contextual clues such as missing λ symbols could be used to communicate to observant players that the base is a trap. Or enemy blood or victims showing an enemy is near, sound too, clues leading to the “thing”, playing detective and then being pleased to see if it was true or not.

Allowing symbolic assets and geometries to stand out from other information.

Spend your art efforts where players will see it the most.

Design your own ruleset and stick to it.

Chapter 5: Introducing Emotional Level Design through Survival Instincts

Player’s desire for a game to continue.

Creating dramatic tension through close calls with failure.

Gamespaces that players will want to protect.

Power-ups to enhance characters beyond their natural state of weakness. Our own quest for natural growth. Powerful enemies or an environmental obstacle they cannot cross. Easily overcome dangers it once thought insurmountable.

Regenerating health diminishes the pleasure of finding hidden objects but allows to focus on challenges and quickly continuing. In games where resource management is dealt with through regenerating systems, levels tend to be very linear and focus on ushering players from one challenge to another. In games where the game state can change depending on the player’s amount of resources, level design can be used to create the opportunity for dramatic moments. Risk losing health so they may explore for powerful rewards.

Refuge spaces provide protection from external dangers and a place from which to plan how to move forward. These spaces can create exciting gameplay scenarios when used in proper sequence: running from cover point to cover point in a shoot- ing game, moving from one hiding spot to another in a stealth game, and many others.

Lower ceilings create the feeling of greater protection.

When utilizing prospect and refuge gameplay in this way, enemies become important architectural elements and the level itself a spatial puzzle.

Wright-esque details and natural materials to create a secretive, organic look.

Moving debris with the Gravity Gun weapon to create bridges between rocky cliffs.

If a space is too large or too small, it is uncomfortable. However, if a space is accommodating to the abilities of a human or game avatar, it is pleasurable.

Shade is accomplished by allowing diffused lighting into a space through curtains, screens, or stained glass. It was a major feature of Gothic architecture, which strove to create an ethereal experience called lux nova, or “new light.” Incomplete visual information entices humans to explore and complete their knowledge of what they see. Combined with shade, the result is a nearly inescapable need to explore.

The player is unsure of whether a space is safe or unsafe due to a combination of friendly, unfriendly, and ambiguous spatial indicators. Carlos Scarpa’s Castelvecchio Museum in Verona, Italy (1972– 1975), features openings between adjacent gallery spaces that entice both through rhythm and the obscuring of what is to the right and left of each portal. Zelda games often use a combination of shade and prospect spaces to create ambiguous dungeon environments: is the player about to receive an important item or be attacked?

This mirrors the friendly associations shadows hold for writ- ers such as Junʼichiro Tanizaki, who, in his essay In Praise of Shadows, reflects on the Japanese’s relationship with shadows in their aesthetics, praising their subtlety and contemplative nature against the garish shine and brightness of Western objects.

Shadows can also be used to create linear elements on surfaces parallel to the player’s line of sight that pull the player toward their endpoint.

Shadows’ harmful associations should also be noted.

The psychological effect of the unknown cannot be ignored. Creating anxiety by making players unaware of what surrounds them. Spielberg withheld a view of the film’s monster, a great white shark, for an hour—showing only views from the shark’s perspective whenever it was stalking bathers. This decision on Spielberg’s part made the shark synonymous with the water itself.

While it is common to have a fear of heights, heights can also give a strategic advantage by allowing occupants of high places to look down on opponents below.

After surviving the walk across the beams, players can look down upon their next major challenge⎯the prospect-refuge courtyard. This allows players to scout the enemy patterns as though looking at a plan of the level.

The ability to continue playing being a very powerful reward indeed.

(dropping clues for the player to think about while she solves other problems)

For example, at any given time the player should have at most three outstanding problems to solve (where problems are things like a locked door, a combination lock, or the location of an item). These problems can be solved in any order, and once they are solved a new set of problems will be presented.

When those choke points do arrive, we try to make the next step as obvious as possible.

In the order that they prefer, but stays within the progression structure that we’ve defined.

Close off paths that are no longer relevant to the game.

Chapter 6: Enticing Players with Reward Spaces

If challenges are what make games dramatic, rewards are what make them pleasurable.

This places responsibility for finding the path in the hands of the player, giving him or her a mystery to solve.

The player gets clues that a reward may be nearby and is thus curious to see if the reward is indeed there. This can be accomplished with the use of modular assets, textures, lighting techniques, or anything that can be prefabricated and reused throughout a game as a symbol. If players are rewarded for exploring spaces of a type or with certain visual elements, they will learn to recognize that rewards may be nearby if they recognize similar areas later in the game. This will make them curious to explore.

Rewards of glory, Rewards of sustenance, Rewards of access, Rewards of facility.

While in level design we are concerned with the placement of these reward items in space; as discussed in using rewards for entice- ment, there are types of level spaces or experiences that can themselves be rewards:

Reward vaults:

these spaces frequently distinguish themselves from other level spaces in terms of lighting, music, or spatial character. They are often intimately sized and may feature high ceilings or vaulting, the use of arches to create a ceiling or roof, to architecturally celebrate the space.

Rewarding vistas:

Providing a moment of catharsis after areas of high-action gameplay. With an interesting visual asset or animation to look at, players will pause for the intended rest. Celebrate spatial achievements such as climbing high structures.

Meditative space:

These spaces offer a relaxing atmosphere with soft lighting and the sound of water. Portal has players use elevators to travel between puzzle chambers. These spaces offer neither rewarding views nor resources, but break up gameplay so players may mentally recover from the puzzle they just completed and prepare for the puzzle to come.

Narrative stages:

Games often utilize narrative as a form of reward. Reserve the most significant story elements for epic architectural set pieces. Leave a combat mindset, rest, and prepare to absorb narrative information. Epic narrative events of games may occur and serve as easily identifiable spatial goals. Give players a sense of achievement and prepare them for upcoming high-intensity gameplay.

Spatial denial—the act of withholding rewards from players. This denial of a wide view makes the limited experience more rewarding. Experienced for a short while and does not treat it as a destination, allowing the landscape to keep its experiential power.

Incite curiosity: the brain will assume the identity of the incomplete information and seek verification. Obtuse angles can be utilized in games to partially reveal rewards, enemy encounters, or other important events. They can hint at or warn of things to come, or elicit exploration by offering players ambiguous information. This creates a sense of risk.

Visitors to temples and houses must often pass through several layers of garden space, each meant to separate visitors from the business of the outside world and spiritually cleanse them before reaching their destination.

Each wall layer has an opening through which Link may shoot arrows at the switch. While providing a method for the player to progress through the puzzle, the voids in the wall also reveal the player’s destination.

Spaces laid out according to the principles of oku have winding layers of walkways that conceal but hint at places for gathering and rest. Oku spaces utilize many different types of denial to create a powerful sense of curiosity.

Super Mario Bros. and many other games retain player interest because they have long-term goals, short-term goals, and allow opportunities for player-defined goals.

The Rod of Many Parts, a story structure in which characters must collect seven parts of a magical artifact.

Anticipate upcoming rewards. In many ways, this resembles the classical conditioning practiced by Ivan Pavlov.

“Just one more”

Players may even be motivated to explore the room in which they expect a reward if they do not find it immediately accessible.

Chapter 7: Storytelling in Gamespaces

Players to create their own stories through gameplay.

Donald Norman, in his book Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things, discusses his collection of three unusual teapots, each having a significant narrative or experience.

What the important narrative elements of your game are, what actions will support the narrative, and whether those actions can be translated into gameplay mechanics.

Emergent narrative. As players engage the rules of a game system, they create their own series of events that drives the game action forward. Designers may guide players toward intended emotional responses, even if the exact experience of these responses is different for every player.

Embedded narrative spaces, spaces that contain narrative information in the architecture itself.

Cinematography is the study of film techniques, though it is often used to discuss the composition of scenes on film. For game design- ers, the relationship between camera and object position can be a powerful tool. When discussing camera usage in games, we discovered that an important element was drawing a player’s attention to environmental elements the designer wished him or her to see. In first-person games, this often includes drawing the player’s view to objects with visual components such as lines, contrasting colors, or lighting.

Games often utilize materiality, specifically in the tile art or texturing of a game’s level surfaces, as an indicator of a place’s character and place along a hero’s journey.

In many ways, movement through a game’s narrative is its own reward.

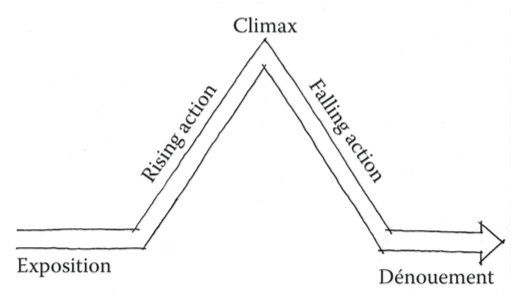

Freytag’s pyramid shows the stages of the dramatic arc.

Rewarding Exploration with Embedded Narrative.

Falling action and dénouement are both important elements of this structure for game designers, as they are opportunities for players to slow down and breathe. They are also where we can position rewards for players: a dramatic escape, an item that replenishes lost resources, or a sought-after artifact.

Reward players with optional narrative for exploring gamespace on their own. Giving access to privileged information.

Chapter 8: Possibility Spaces and Worldbuilding

Designers cannot directly control the behavior of a product’s users, but can control the rules of a system that users interact with.

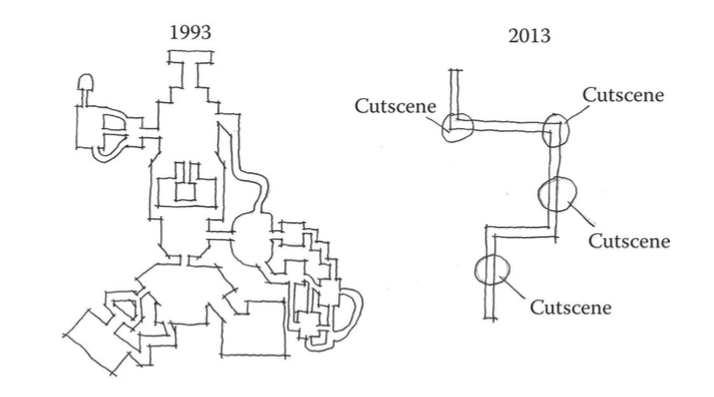

A re-creation of a popular Internet image that describes the seemingly complex nature of older first-person shooter maps compared with the linear nature of modern ones.

Japanese gardens: miniaturized worlds in which occupants can explore a “multiplicity of landscapes” within a short period of time. Clear boundaries.

Miniature Gardens are scale models of bigger phenomena. Fish tanks and gardens are scale representations of systems bigger than people.

In the first screen from Super Mario Bros., the player can see a variety of important symbols from the game, as well as an enemy and a power-up item.

Show viewers outside what is contained within. Upon entering the building, the museum exhibits are revealed on a series of stacked floors arranged like a collector’s shelves (Figure 8.8). The building provides a summary of its contents with this reveal, but rewards those who explore further with more information.

The overview gives a summary of what is contained within each section of the building but denies full understanding of each exhibit unless the visitor penetrates further into the space.

Teasing gameplay to come.

In the West, he observes, many Japanese gardens utilize vernacular Japanese architecture: pagodas, torii gates, lanterns, etc., to give the garden “a Disneyland quality.” However, the true purpose of such gardens is to give the impression of natural landscapes in a small, explorable area.

Creating landscapes in accordance with how they occur in nature helps give landscapes their individual character, or yo.

Putting boundaries on this system in a miniature garden helps define the possibilities of a gamespace.

Like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the experience of Minecraft begins as one of linear discovery and becomes one of freedom within a defined world. Both works show how one introduces the element of choice in many games by initially guiding players through the rules in a directed or limited manner and then allowing players to explore on their own.

Carefully limit player choice at first and slowly reveal new possibilities as players master each part of the game. Imposing limited boundaries at the beginning and expanding them as players learn the game. Framing portions of the world and possibility space into districts helps players master a few commands, and then move on to new ones when they are ready for boundaries to be pushed aside.

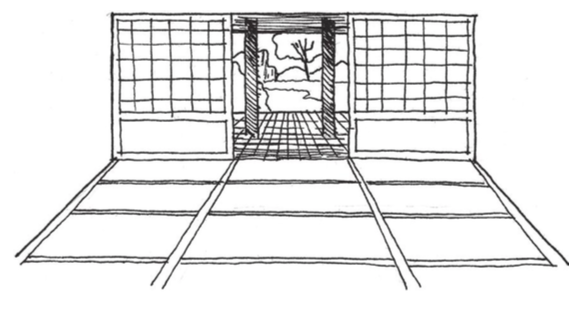

The edges of individual mats work much in the same way that horizontal shadows do, drawing the user’s eye across the horizontal plane of the floor and into the outdoors, which are revealed by an open shoji.

A reward is given first for something simple and then for increasingly complex steps. She argues for each action to be taught one at a time in isolation.

“What if something appears that should not, according to our game rules, exist?” When designers establish rules, they should also be open to the idea of breaking them in ways that do not break the logic of the game, but instead provide exciting discoveries for players.

Chapter 9: Influencing Social Interaction with Level Design

In terms of construction, the shops of vendors or trainers within in-game urban spaces utilize consistent symbolic assets: building types and signage. In this way, players of each class can form a language in which symbols are important to them, and seek out these symbols.

the player’s ability to customize his or her own place in these worlds, whether by establishing relationships with specific players or customizing his or her own surroundings, encourages a sense of belonging.

Chapter 10: Enhancing Level Design with Music and Sounds

Audio can entice player movement, help set an atmosphere for gameplay, or reward players for their achievements.

Rhythm, the timed repetition of elements or movements.

Music is the unseen character. It’s the emotion behind the actions of a player. It’s gently there to show the game designer’s intentions. It’s totally collaborative with the developer.

Music offers emotional cues to players.

Blurred the lines between the game’s music and the sound effects of the game’s world.

Extremely minimalistic music throughout the game (metroid 2). The music is often more like rhythmic ambient sound, with electronic cave sounds and the noises of creatures as the instruments.

Level designers should seek to accompany their scenes with music that best conveys the mood they wish to create.

In biomusicology, there is a concept known as entrainment, where an organism syncs itself to an external rhythm or to other organisms.

If players are aware that bonuses occur every two levels, they will pay extra money to continue after dying.

Even small architectural details like the spacing of floor tiles in a shopping mall can factor greatly into user entrainment. People will widen their pace and move faster over wide floor tiles, and slow down as they shorten their pace for smaller tiles. Floor tiles are commonly smaller near expensive items. This makes shoppers slow down as their carts begin clicking on tiles faster, creating the feeling that they are moving too fast.

Where 2D sound excels at establishing the atmosphere of a gamespace, 3D sound calls attention to specific areas of a level.

Portal uses a similar tactic to alert players to secrets: radios playing an instrumental version of Jonathan Coulton’s Still Alive are strewn throughout levels. By offering in-game achievements to players for finding them, the developers turn listening for a specific song or sound into an exploration game of its own.

When creating especially powerful enemies or placing them in levels, giving them unique sounds can add further tension to encounters with them.

The concept of interactive sound as being event-driven suggests that events are repeatable—that if we repeat the action, we will receive the same reaction.

Weapons in many games often play satisfying effects when used: loud bangs for guns, explosions for rocket launchers, and clangs for swords.

If we are to consider sound effects in games as symbolic assets, we have to understand how they produce feelings of agency for player activity. In terms of characters, a pleasant “bwooop” when a character jumps and a jagged “err err err” buzzer when characters are hit become positive reinforcements and punishments, respectively, in response to player actions.

In Year Walk, players must at one point navigate a cave by selecting from an array of identical pathways. By listening for specific notes at each path, players can discern which way to go. The notes that lead players in the proper direction are pleasant and in major keys, while the notes that return players to the beginning of the cave are in harsh minor keys.

Symbolic game objects can have their own symbolic audio assets. Levers can make a satisfying click when pulled, doors can open with a heavy grinding sound, etc. When played in response to player actions in a level, they give the impression that the player has somehow greatly affected the gamespace.

Difficult puzzles triggers the playing of more triumphant audio assets.

The sound played in a reward vault, rewarding vista, or meditative space may have a relaxing melody when compared with the intense rhythms that possibly accompanied any preceding challenges.

The careful use of these types of evocative music and sound assets greatly enhance the material reality of gamespaces and the experience of interacting with them.

process based on lots of playtesting

Chapter 11: Real-World Adaptive Level Design

Today, the games discussed would be called serious games, since they model real-world scenarios in such a way that they train players to deal with them.

Enhancing specific spatial experiences with games and utilizes them as tools for enhancing parts of everyday life.

To educate people about alternative ways to address world problems, Buckminster Fuller created the World Game.

As tracking systems, Life Quest and Onward transform the concept of a to-do list into gameplay.